Jonny Steinberg calls Anthony Altbeker's The dirty work of democracy "one of those rare books that transcends its subject matter and tells us something about the state of a country's soul."

Mhambi agrees.

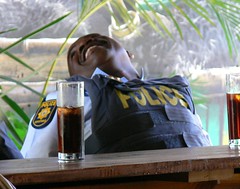

Altbeker spent a year with the South African police, attempting to understand the challenges of policing at the coalface. The book documents his year.

If this book was a documentary, it would be cinema verite. Obeservational documentary, where, from what you see and hear you can deduce allot more than a narrator ever could tell you. And boy is the prose beautiful.

But The Dirty work of democracy is not a didatic free zone. Often Altbeker includes incisive analysis on the nature of policing, South African violent crime, the frustration felt by the cops, the feelings of unwantedness he encountered among white cops, pervasive corruption, whether crime is falling and to what extent South African police can actually address the problem of crime. With most of his analysis Mhambi is in agreement.

But because he does give his opinion on some issues, Mhambi was left with the impression that Altbeker chose not to expressly say some other things. Uncomfortable things that he perhaps hoped we'd deduce ourselves from what he were describing.

Altbeker points out that society gives police the exclusive right to use coercive force to sort out those situations, those conflicts that arrise when many people share a common social space. It is a precondition for a viable society.

One learns that an inordinate amount of time is spent by the South African police sorting out citizens domestic problems. A situation for which they are ill-equiped and that saps their energy and time. But domestic violence also drives much of the countries homocide rate.

No more ubuntu

Altbeker is confounded by an area - Maluti - where lack of the state's presence by way of police and its crumbling roads, had not stopped it from having half the national average homocide rate. All large and anonymous societies needs its intitutions, but: "In the smaller, more settled communities of the past, the simple fact that everyone knew everyone else is enough to keep the peace. Whatever we tell ourselves about the strength of social bonds in our communities and the power and currency of ubuntu, those days are gone forever."

Anonymous predadory crime

Another revelation, is how hard it is to solve a crime where the perpetrator is unknown to the victims without catching the criminal red handed. Altbeker tells how two Rosebank cops dithered - in his presence - while a violent robbery was in progress. The result is that criminals that could be accosted, escape. Altbeker justifies this behaviour: "

With anonymous predatory crime, witness statements are often so general that its of little use, and physical evidence like fingerprints and DNA unlikely to lead to tracking down a criminal.

A raw untamed force

For Altbeker, visits to places like gang infested Elsies river, showed how power operated like a raw untamed force. The courtesies demanded by our law of law enforcers, had no place in these communities. "They simply gained no purchase". He also qouts V S Naipul, to explain that these communities may live vicariously through the glamour and power of the gangs.

People are the cause of crime

Then in Ivory park an Inspector Mokhosi tells him - after they investigate one of many murders - simply: "People are the cause of crime." It's not only poverties fault, because says the inspector, he comes from a poor background. "There is something wrong with them."

Sphere: Related Content

Friday, November 24, 2006

The dirty work of democracy (part 1)

Posted by

Wessel

at

8:04 am

![]()

Labels: corruption, crime, CrytheBelovedCountry

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment